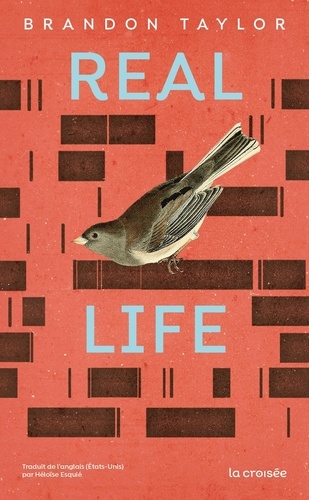

Real Life – Brandon Taylor

“Real Life” was recommended by my friend Najam, who sent me a whole bunch of queer fiction titles he’d been reading. I already read Brandon Taylor’s Substack pretty religiously. He’s partial to fiction with characters who care about something, whose way of making sense of the world is legible even if they don’t make sense of the world the same way you, the reader, do. He’s criticized modern novels that have characters who don’t really have any ethics, which is really characters who are so self-absorbed that they can’t get out of their own heads, and I truly appreciated that critique. I’m tired of it! It’s a boring trait in people and in characters. Give me a little passion over the passionless, soulless character any day. I’m not saying I need every character to be a zealot, but I do need them to have something that they desire, something they want to gain or don’t want to lose, a relation to the other characters around them that matters.

So Brandon Taylor already has a special place in my heart simply for his clarity of criticism, and his passion for pedagogy as an educator. One day, a few weeks after Najam recommended “Real Life”, andie and I went to a small table sale run by an acquaintance whom she’d met at a protest of Henry Kissinger’s funeral, and they were selling used books, which is how I wound up buying a copy of “Real Life” that already had a few underlines in it. The truth is that after reading Taylor’s Substack for a few years now, I wanted to see if his fiction actually measured up to his teachings. I can acknowledge that this was maybe a high bar for the book to clear, since his teachings and essays have been pretty influential in how I think about not just fiction, but art as a whole.

It’s been a few weeks now since I finished the book, which I devoured in that way you devour something when you simply need to see what happens. It was a difficult read in a few ways, which I’ll get into more in a second, but the main character, Wallace, has stuck with me. One of the markers of a good book of fiction, to me, is when a character has that quality of being truly alive, that quality which makes me think of them occasionally long after I’ve finished reading the book. Cathy and Heathcliff were alive in “Wuthering Heights” (the narrator was not, at least to me). Tracker in Marlon James’s “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” was incredibly alive to me, almost containing more life than one person could possibly bear. That’s what I liked the most about “Real Life”; Taylor created a character who lived and breathed, who had a history that was real and who carried that history with him, who cared about things, who struggled with those things he cared about.

Wallace, a 20-somethingish Black man who grew up poor in the south, is placed by Taylor into the stiff, uncaring world of scientific academia, as a PHD student in some predominantly white Midwestern town. The book is him uncomfortably navigating this setting while all his sometimes well-meaning, sometimes cruel white classmates manage to fuck him up in various ways. And the book centers around the incredibly painful, masochistic relationship he has with his white, boyishly lanky classmate who once said some racist shit to Wallace and says he’s straight even as they start to have sex and fall into something approaching a relationship. It’s hard not to grind your teeth as Wallace gives into the desires of those around him, floating through his complicated grief at his dad, who he hated, passing away, bottling his bitterness at the hatred and racism and cowardice of his classmates in the meantime. His responses make sense from a character level, though — this is someone who has never really processed a lot of traumatic childhood experiences, who is just trying to hang onto his one attainable prospect of making enough money to be comfortable in American life, even if he has to put up with a lot of bullshit to do it. I didn’t identify personally with a lot of Wallace’s detached way of seeing things and pent up feelings which he had nowhere to put, but it all made for a real, believable character, one who was constantly breaking my heart.

There were things about the writing that made me cringe, or want to put the book down sometimes. I would personally be okay not engaging with any narrative set in Midwestern academia ever again. A pet peeve of mine is that writers sometimes can’t get out of their own world enough; at least this academic narrative was based in the sciences and not writing, but still, I would like narratives to revolve less around the white collegiate experience (and even though the main character is Black, there’s no doubt that much of this novel still revolves around the white collegiate experience, or at least is dependent on it as the primary foil). There’s also something I can’t quite name about Taylor’s use of metaphor that doesn’t always hit for me. Metaphor is so tricky; like comedy, it needs just that right balance of the familiar and the unexpected, and I felt that Taylor’s descriptive metaphors were sometimes a little too familiar. For example:

“Dana pants like a winded, wounded animal.”

“The lights of the capitol building are in the distance, white beams turned gauzy, like a dream.”

Do you see what I mean? I appreciate the attempts at descriptive metaphor, but they were not quite doing what I wanted them to do. andie and I often say that the novelists should be trying to write more poetry or that only poets should get to write novels (a little hyperbolic but you know what we mean!), and I felt that there were plenty of good examples here of unpolished metaphors that could have used a little more shine.

My favorite section of the book was when Taylor takes a break from his tense narrative about racist academic life and lets Wallace describe, in furious passages, his history. It feels referential, like Taylor must have been thinking of some specific novel or novelist’s work and been trying to imitate it, though I don’t know what the reference might have been. All the passion comes rushing in at once, standing in contrast to the cold, microscopic lens of the rest of the novel. We learn about how Wallace was abused as a child, all the pain and the tender anger that comes from it. That chapter allows the book to breathe while contextualizing so much of the character who’s head we’ve been living in. I felt that it saved the book, brought everything so much more to life, though after more reflection I understand that I’m probably just partial to thunderous passages more than terse, hushed ones.

“Real Life” was an apt name for the book, and the central theme is very clearly laid out. In the midst of all this racism, all this politicking just to get a degree that will land you a solid job in the sciences, all the competitive jockeying to be in the good graces of the academy, what truly matters? At the end of the day, what will any of these white people stand for? It’s all a game, all fake to them, since most will land on their feet no matter what happens to them in the academy. And so the real life, to Wallace, is somewhere else, somewhere far away from the university halls of this Midwestern town. Wallace teeters on the edge of throwing away all he’s invested in that place, only being pulled back by a fear of losing the opportunity for capital and his new relationship he’s in, even though it’s often terrible. It’s a poignant story; by the end, you root for him to go anywhere, to just get the fuck out and run away. I didn’t quite like the ending, but endings are hard. I would definitely give another book of Taylor’s a try.

Speaking of which, here’s a good interview with Taylor about his newest book, “Minor Black Figures” (version without a paywall, but with some ads, is linked here). Here’s him talking about his style of writing fiction versus his students’:

It’s not objective by any means, but I am trying to create a representation of society. And it strikes me that this is not true of my students. The representational element that we used to take as inherent to the act of fiction-making – that’s gone. I don’t think that they understand that within fiction writing there is this kind of secret bargain that you’re striking, that you’re representing a reality. I don’t think that that’s a thing on their minds anymore. I don’t think they’re representing anything. It’s the closest we’ve come to pointillist realism maybe. It’s kooky. It’s wild.

What I appreciate most about Taylor’s writing and interviews is that, even if I don’t always think he’s right, he cares deeply and he thinks about art a lot and he’s not afraid to be funny, even about the things he’s taking seriously. I’ve watched his thinking evolve over the years, too, and I will always appreciate when someone is taking the time to criticize and remake themselves.

Say hi!